Call 0330 880 3600 Calls may be monitored or recorded. Opening Times.

- TRAVEL INSURANCE

- COVID-19 ENHANCED COVER

- More Options

- Help & Advice

- Existing Customers

Call 0330 880 3600 Calls may be monitored or recorded. Opening Times.

1. Malaria About

Malaria is a serious infectious disease that affects both humans and animals. The disease can be fatal and is responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths annually.

The latest figures from the World Health Organization indicate there were over 200 million documented cases of malaria and almost 500,000 recorded deaths from malaria in 2015.

These figures are derived from records taken around the world, however, actual figures are likely to be substantially higher.

Although there is no malaria in the UK, around 1,500 Brits a year catch malaria whilst abroad and of these cases there are around three fatalities. Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites that have entered the bloodstream. Malaria is medically termed as an acute febrile illness which means that is characterised by the sudden onset of fever.

Malaria is predominantly spread via the bites of infected mosquitoes. Only one type of mosquito transmits malaria. Female Anopheles mosquitoes carry malaria and, like all mosquitoes, they are most active between dusk and dawn.

Infected Anopheles mosquitoes are sometimes referred to as ‘malaria vectors’, meaning organisms that transmit malaria. Malaria is very rarely spread through blood transfusions and shared needles. Malaria is not contagious between humans or animals.

Where can you catch malaria?

Malaria is found in approximately one hundred countries, putting almost half the world’s population at risk of infection. Around ninety percent of malaria cases are contracted in Africa and the disease is particularly common in countries with tropical climates. You can catch malaria in the following parts of the world:

If travelling to any of these areas you should arrange an appointment with your GP or travel nurse as soon as you know you will be travelling or at least a month before your departure date.

2. Malaria Prevention

When travelling to a country where malaria is endemic, you should obtain advice from your GP or travel nurse. If necessary, you will be prescribed preventative antimalarial drugs. These reduce the risk of contracting malaria by about ninety percent.

Pregnant women should only travel to countries with a risk of malaria if absolutely necessary because malaria can cause severe complications in both mother and baby. In cases where a trip cannot be cancelled or delayed, a doctor must be seen to obtain preventative antimalarial drugs suitable for pregnant women.

Malaria can be contracted from a single mosquito bite. As antimalarial drugs do not completely eliminate the risk of infection, it is crucial to try and prevent mosquito bites.

Wherever possible:

People who live in areas with high levels of malaria sometimes develop partial immunity. It is important to note that this immunity is not permanent.

Even if you have previously lived in a country with high occurrences of malaria, immunity quickly diminishes. As such you should take the necessary precautions when returning to that country or another country that has malaria.

There are several different antimalarial drugs that are used to help prevent malaria. All types must be taken prior to travel, throughout your stay and after your return. The duration varies according to the type of drug prescribed. The most commonly prescribed antimalarial drugs are:

While some of these medications can be purchased without a prescription, it is advisable to seek the guidance of a doctor or travel nurse as some may not be suitable for you. For example, you may be more prone to side effects from some drugs if you:

3. Malaria Symptoms

Malaria has an incubation period, so symptoms do not develop until seven to eighteen days after infection. However, with some strains of malaria, it can take up to one year for symptoms to develop.

Malaria parasites reproduce in the liver and spread into the bloodstream, destroying red blood cells. Typical malaria symptoms are not dissimilar to those of influenza and common viruses, making it difficult to diagnose in some cases. Early signs of the disease are:

Some strains of malaria are cyclic, with symptoms occurring in 48-hour cycles. Chills and shivering are followed by fever, sweating and fatigue. The symptoms last for six to twelve hours and the cycle repeats every third or fourth day.

If undiagnosed or untreated, milder forms of malaria can result in recurrence of attacks over the years following infection. The body may gradually develop its own defences, eventually reducing the severity of the attacks.

The most serious strains of malaria can cause life-threatening complications and fatality if untreated. Advanced malaria symptoms include:

If you think you have contracted malaria you should immediately seek medical assistance. Remember that symptoms of malaria can develop up to a year after travel. A simple blood test will be carried out to check whether you have malaria.

If malaria is confirmed, treatment will commence straight away. Malaria is serious and symptoms can worsen rapidly. However, when treated promptly, most people make a full recovery.

Prior to travel, tell your doctor or travel nurse if you will be travelling through remote areas where there may not be access to medical care. In such cases, you will be prescribed emergency standby treatment in addition to preventative antimalarial drugs.

4. Malaria Treatment

All strains of malaria are curable, but they must be treated as soon as possible. If malaria is not treated early enough, life-threatening complications can occur and it may not be possible to make a full recovery.

There is not currently a commercially-available vaccine for malaria. Over twenty vaccine constructs are in preclinical development and clinical trials, of which ‘RTS,S/AS01’ is the most advanced.

S/AS01 must be administered via four doses over a period of eighteen months and efficacy rates are relatively low. In trials conducted on approximately 15,500 young children, malaria was reduced by thirty-nine percent which means the vaccine prevented four in ten cases.

Obstructions to the development of a malaria vaccine include:

A Malaria Vaccine Technology Roadmap has been developed by global health organisations. Its goals include creating a malaria vaccine by 2025 that has an efficacy of over eighty percent and a protection duration of more than four years.

In the majority of cases, the same types of drugs that are prescribed to prevent malaria are used to treat the disease. However, in cases where preventative antimalarial drugs were being taken, the same drugs cannot be used to treat it.

Therefore it is imperative that you know the name of the preventative antimalarial drugs you are taking, or were taking during your trip if symptoms occur after your return. A combination of antimalarial drugs may be prescribed for strains of malaria that are resistant to certain drugs, like super malaria.

Antimalarial drugs are usually administered orally via tablets or capsules. When symptoms are very severe, medication is administered intravenously via a drip. Treatment can last several weeks and leave you feeling weak and fatigued.

Treatment has a high success rate, with full recovery expected in those who are treated in the early stages of the illness. If malaria remains undiagnosed or untreated for a long period, treatment may not be wholly successful and complications or death can occur.

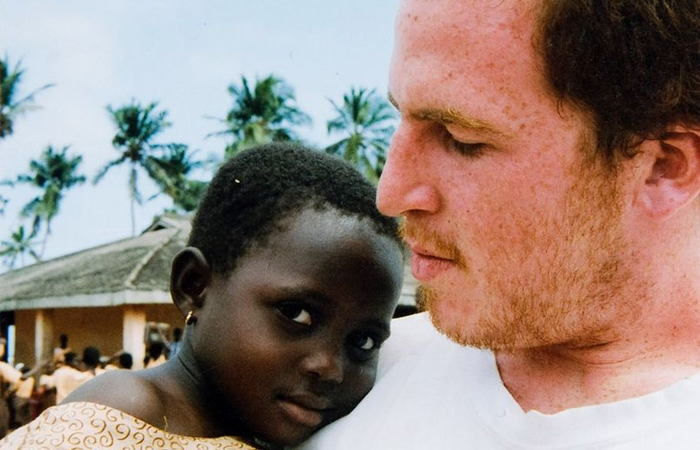

Jo tragically lost her son Harry to malaria when he gave away his malaria pills while volunteering in Ghana. Her story of overcoming loss and adversity inspired a character in a film written by Richard Curtis and has taken her around the world campaigning for malaria awareness. Here is her story.

“In August 2005, my son Harry tragically died from a preventable disease which costs less than a cup of tea to treat, he was just 20 years old when he died from malaria. Harry had been volunteering in Ghana and had loved every minute of his four-month experience, but just before returning home he gave away his anti-malaria medication to the young children and his girlfriend in the village, believing that they needed it more than he did. Sadly, this was a decision which cost Harry his life.

When Harry came home, he appeared healthy and happy, little did we know at the time that he was already suffering from malaria. Yet, 10 days later, he became very unwell and was admitted to our nearby hospital, where after several hours of blood tests it was confirmed that Harry had contracted the most severe form of malaria – falciparum malaria. He was quickly admitted to intensive care. Yet, throughout this nightmare we continued to be positive, believing that Harry would be okay, this was the UK after all and the doctors would be able to treat the disease. But malaria is not a disease which discriminates and less than three weeks after returning home Harry had died.

Since Harry’s death, I have done everything I can to try and stop other parents from enduring the heartache that our family experienced. In 2009, I became a Special Ambassador for Malaria No More UK, a charity that works tirelessly to inspire public support and political action to save lives. I was able to visit the village where Harry had spent his final few months in Ghana and see the great work of Malaria No More UK.

It’s really inspiring to see the progress being made – child deaths from malaria have been more than halved since 2000 and we have the chance to end malaria within a generation. Travelling is a great adventure and one which I would recommend to anybody, yet it is important to follow the recommended advice from your doctor before you travel. I have learnt so much with Malaria No More UK, namely the importance of malaria prevention and following simple steps such as knowing the risks before you travel; taking the complete course of malaria prevention tablets; sleeping under a mosquito net; protecting yourself with DEET and wearing long, loose fitting clothing. These are basic, no regrets steps. Yet, as shown by Harry’s story, the importance of completing your course of anti-malaria medication cannot be ignored. This simple decision is one that in the end cost him his life. Please take a look here before you travel”